Seasteaders have launched companies on both sides of the planet.

Singaporean Shiwen Yap worked with The Seasteading Institute in an official capacity from 2014 to 2016, publishing titles like Seasteading has enormous potential in Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan, Seasteading & the ocean economy: Untapped drivers for Singapore’s economic growth, and The blue economy and seasteading: A key growth driver for Singapore (behind a paywall at The Business Times, but you can read here).

Shiwen partnered with Netherlands-based FlexBase BV, founded by Jan Willem Roël, to launch FlexBase International. Since then, he’s advanced the venture. They approach floating structures from a unique angle. Focused on floating structures with foundations built using a proprietary EPS-concrete hybrid, the idea is to develop very large floating structures (VLFS) as a form of marine urbanisation. It’s about VLFS as an extension of the cityscape and an adaptation to rising sea levels. Patri Friedman, the founder of the Seasteading Institute and board chairman, is leading a funding syndicate on AngelList and is an investor in FlexBase International.

Want details? Read Shiwen Yap’s in-depth interview with The Seasteading Institute below. I think you will find it exciting.

1) What’s the story behind FlexBase International and how it spans Singapore and Rotterdam?

We are a climate change adaptation company. We provide floating foundations and the expertise to develop and maintain floating structures to adapt to the hazards that coastal cities face from rising sea levels.

FlexBase BV was founded in the Netherlands in 2013 after many years of R&D by Kingspan Unidek and Dura Vermeer. Singapore-based FlexBase International comes from a collaboration of myself, Shiwen Yap, former ambassador of The Seasteading Institute in Singapore from 2014 to 2016, and Jan Willem Roël, the founder and CEO of FlexBase BV who was looking to internationalise the FlexBase business.

Together, we initially linked up with a floating renewables developer with shipyards in Singapore, Kim Heng Ltd. We also established a research partnership with the National University of Singapore (NUS) through our work with Dr Paul Ong of the civil engineering department there. During the last three years we have been mentoring Honours Thesis students for different applications of the FlexBase system in ASEAN.

2) Where’s the company in its business lifecycle and its major challenges right now, especially with the global pandemic?

We are currently raising capital for our seed round. We already developed a portfolio of projects in the Netherlands and other countries such as Bangladesh and the Philippines.

The product-market fit is established, with regulations based on institutional knowledge and proven models in the Netherlands. The foundation of the Rotterdam Floating Pavilion was built by FlexBase, and that is the most visible and awarded project.

At this stage, our aim is to raise funds for developing a research hub and Indo-APAC HQ in Singapore, as well as to serve as the international hub for holding the IP. We are quite interested in the markets of Thailand, Vietnam, Singapore, India and the general Indo-APAC region. But if opportunities arise in other countries, we are of course open to discuss.

The major challenge is the regulations. Outside of the Netherlands, there are no regulations for floating structures. The Dutch have developed this technical agreement, NTA 8111, as a floating construction code. In the Netherlands, more and more floating structures (especially floating homes) are being implemented in urban plans.

This involves factors such as the accessibility of floating structures; connection of utilities; water level fluctuations; water quality water management; fire safety requirements; and various other elements.

The minute you apply naval architecture and conventional marine engineering guidelines and regulations, the economics simply don’t make sense. A separate code is essential to realising marine urbanisation with floating structures.

3) How do you see the economic potential of floating structures and where in the world do you see it playing out?

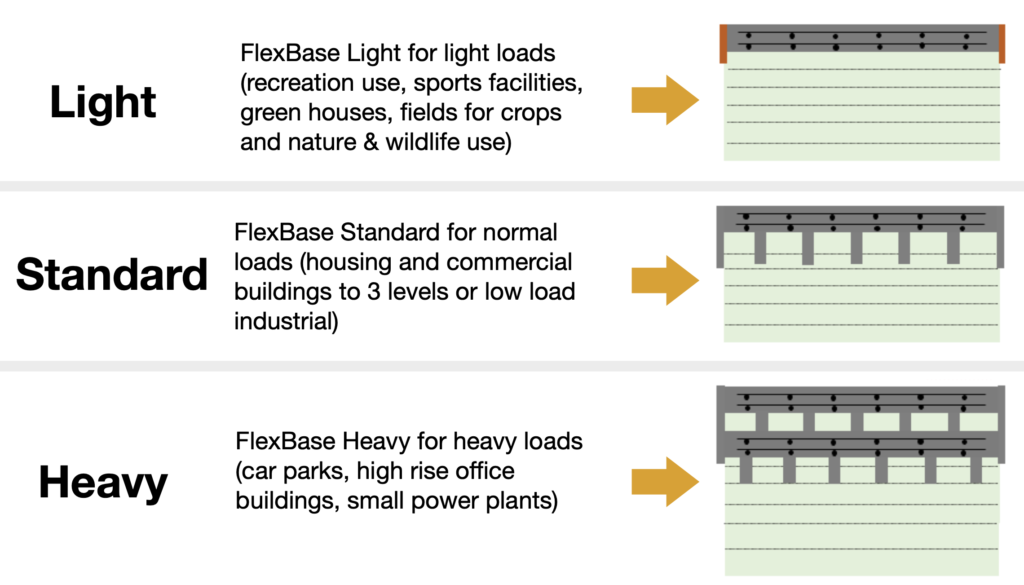

The FlexBase Concept System is fundamentally a proprietary expanded polystyrene (EPS)-concrete hybrid whose materials can be locally sourced for building pontoons. So, costs of production are low, and it is highly suitable for near-shore coastal and inland waters. We did a cost estimate in 2019 with Kim Heng Ltd. and discovered that for the equivalent structure in steel, we were 35% to 60% cheaper. This radically changes what is now possible on water.

With the EPS-concrete hybrid, there are also substantial operational cost advantages. Besides the advantage of not having to worry about rust and refurbishing a steel pontoon every five years, the EPS is laminated in polyurea. So even if the pontoon is damaged or its integrity compromised, it still floats! You can think of FlexBase as being like a surfboard: unsinkable. On top you can build anything and everything, even high density buildings.

All the concrete and EPS required for building it can be sourced locally, reducing the carbon footprint overall. At the end of the lifecycle of the structure, which is more than 50+ years, it can all be 100% recycled. In terms of impact, this can play out anywhere in the world that has to mitigate the effects of rising sea levels and other hazards such as heightened storm surges. Anywhere there is water, floating infrastructure employing our solution is possible.

4) What’s the plan for scaling this up and monetising all this VLFS and sea estate?

Sea level rise grows, and the increase of land subsidence and land scarcity affect the overall market. Coastal cities will adapt to this by following the Dutch model of “living with water”. FlexBase IP licensing and know-how training can be replicated and scaled to meet global needs, whether through JVs, licensing, or franchising.

The first phase of our business is about offering development services for floating foundations, with us working with architects and developers. The initial floating structures are owned by the buyers, we provide the feasibility appraisal, design services and the guidance to build the structure along with licensing the IP. We intend to function on a “design build transfer” (DBT) model for the first phase of our growth.

As we build more structures and achieve economies of scale, we will develop our library of standardised designs. The second phase of the company is to develop an asset management unit. At this stage, we will adopt a “design build own operate maintain” (DBOOM) model, where we own our structures and then lease them out while holding their ownership in a business trust. An on-water real estate company.

5) Where do you see floating cities coming into play?

Floating cities will only happen once you have clear regulations drafted and established for floating structures. To reiterate, you can’t apply naval architecture and marine engineering guidelines to VLFS, because the context is different. Just ask the MS Satoshi guys about this. You’re discussing the use of VLFS and other floating infrastructure in the context of marine urbanisation.

Floating cities will take off once you have the public sector able to perceive it as an imperative and response to rising sea levels, with the regulations in place and engineering codes to de-risk floating structure projects.

When coupled with interest in property investment, floating structures can then be positioned as an alternative asset class that is dividend yielding. This can certainly appeal to a wide category of investors with an appetite for novel investments.

6) What’s the driving force behind the management team for this whole venture?

The beneficial social impact can be realised globally. Rising sea levels are a global issue. Those are the facts. And the other part is the profit imperative of an entrepreneur. We strongly believe in our mission statement: “living with, not fighting water”.

Most of the people who’ll benefit from a solution like ours and overall marine urbanisation are those communities in emerging markets across Asia, Africa and Latin America. They require affordable, economical solutions, and the best way to achieve that is to work with local partners in developing local production ecosystems and expertise.

EPS and concrete can be locally sourced in most countries, and this means we can achieve a far greater impact while also capitalising on local production ecosystems for our supply chain.

It’s also probable that FlexBase could be the ideal solution for any inshore or nearshore startup cities, like that being pursued by Patri Friedman and Pronomos Capital with funding and support from Peter Thiel.

7) How do you plan to deal with the regulatory gap that often exists between the government and developers?

The key here for dealing with the regulation gulf is pilot projects. You need a reference project, something that people can go and see and experience physically. Such projects also need to be the foundation of a regulatory code and to show that floating structures are the outcome of institutional knowledge and proven models.

The pilot project, the first component, is an initial small-scale implementation to prove that a project idea is viable, whether it’s the exploration of a novel new approach or an orthodox approach used elsewhere which is new to a jurisdiction, like floating structures can be. That way, we get everyone engaged, de-risk the entire process and ensure that the regulations we want to push through are adapted to the local context.

The global precedents exist for floating structures in the Netherlands and other communities living on the water across Asia and elsewhere. It’s about translating this to the modern urban setting with all the legal and engineering requirements, and then creating a regulatory/legal baseline that the public sector can work from.

We are lucky in that Jan was involved in drafting the Dutch regulations, so it’s not his first rodeo. Countries like Singapore look for a precedent and then the people behind the know-how and IP. With Jan Willem, we have that. Once Singapore develops the regulations then other ASEAN countries will follow suit as is the Singapore Inc. business model.

8) How do you reckon your company can impact seasteading and the general ambition to build autonomous cities deeper out at sea?

In the space where FlexBase International operates, the focus is on establishing precedents for floating structure regulations and the business case for large-scale marine urbanisation employing floating infrastructure. That can be a beachhead for companies that want to venture into floating facilities further out at sea to support communities. But the economics ultimately need to make sense.

We fully intend to focus on the regulatory discussion and bridging the regulatory gap to enable marine urbanisation. Once we can secure that regulatory code, then there’s a precedent that builds room for manoeuvre with bureaucrats and legislators.

When people see their home cities being extended onto unused sea estate or water space, this opens their idea to the possibility of investing into it. Once you get a floating urban district that is novel and home to different communities, you can build a case for investors looking for alternative assets to back. The key is to focus on selling to the middle class to drive adoption and make it mainstream.

In the long run, our focus on marine urbanisation for inland waters and near-shore coastal waters is a foundation that stakeholders in the seasteading community can capitalise on as traction builds. Once you have precedents established in near-shore coastal areas, then expansion into the deeper seas is a natural evolution of the market.

We are supportive of the seasteading vision and consider FlexBase as a solution for the initial pioneers mainly due to the low costs to deploy. As mentioned earlier we are also looking to securitise the real estate as an annuity investment for ambitious investors, this is likely to be done through some form of blockchain application, so it all fits together nicely in our opinion.

We could envisage Singapore licensing its unique jurisdiction to TSI developers as a means of transcending its physical borders.

9) How will/can FlexBase pontoons reduce the social and economic impact due to the sea level rise due to climate change?

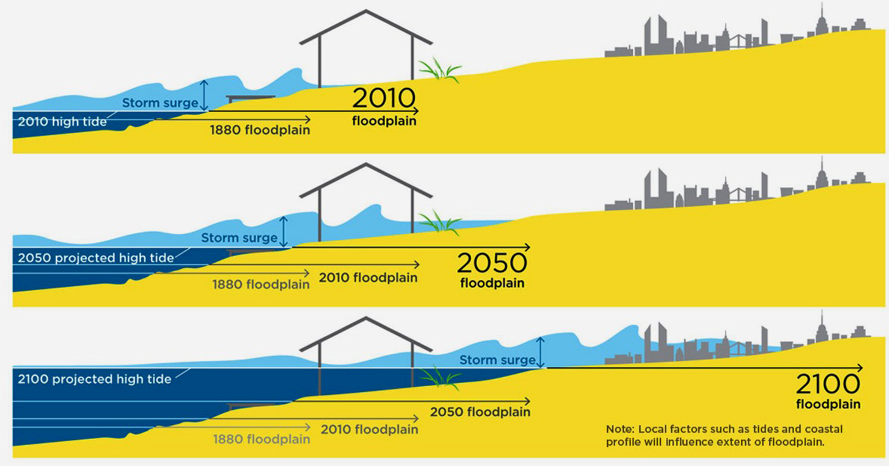

Greenpeace Asia released a report in June 2021, “The Projected Economic Impact of Extreme Sea-Level Rise in Seven Asian Cities in 2030”, and their estimate was that an estimated 600 million people — most of whom are in Asia — live in low-lying coastal regions. These people are going to experience a heightened risk of flooding from a rise in sea levels, and this comes with significant social and economic risk.

Some of the cities in the report like Tokyo and Bangkok are economic centres with significant gross domestic product. And rising sea levels puts pressure on land, population and GDP, fundamental resources of economic development, at great risk.

To be clear, FlexBase pontoons aren’t the only solution. Floating structures made with other materials like high-density polyethylene (HDPE) are part of the solution to mitigate this, and there are other measures that these cities can take. We have the benefit of having a faster time to deploy, with the ability of our floating structures to employ locally sourced materials with a long lifecycle.

What is for sure however is that soon, a new hybrid coastal form will emerge out of sea level rises and learning to live with water. What was once a uniquely Dutch problem is soon to be a global problem. Although in our eyes also an opportunity to respond and assist to reduce the impacts and costs associated with change.

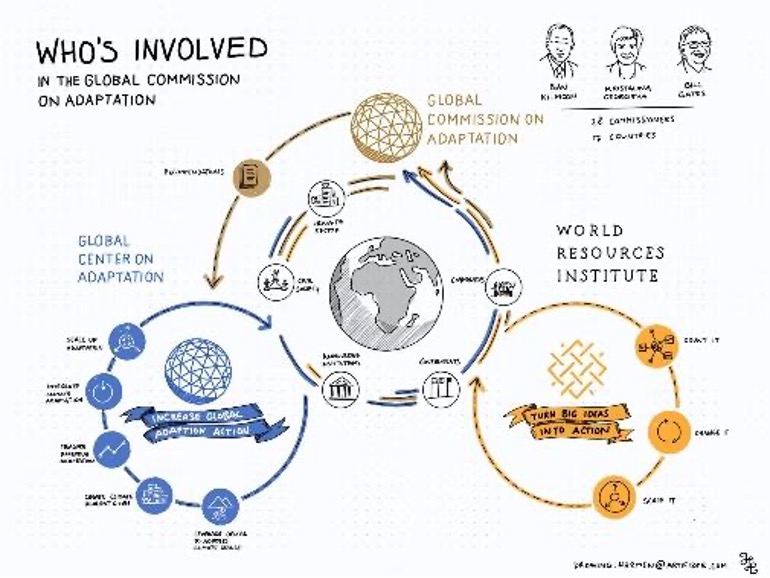

10) You’ve got a connection with the Global Centre of Adaptation with its headquarters in the Netherlands. How does floating infrastructure fit into the overall adaptation strategy?

Floating infrastructure is recognized by the GCA as one the solutions to the worldwide threat of sea level rise, land subsidence and land scarcity. Within the GCA, there’s a consortium of Dutch companies that’s formed a community of practice focused on floating development. These companies have major experience in developing and building floating assets all over the world. We give workshops to the group “100 Resilient cities” and other interested parties on this subject.

11) How does the 2021 IPCC report released on climate change fit into FlexBase International’s overall strategy?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body for assessing the science related to climate change, clearly states the worldwide effects of climate change among them the sea level rise. It will affect all the major cities in the world. Floating assets will be a part of the solution to prevent a social and economic disaster.

A further 15-25cm of sea level rise is expected by 2050. Beyond 2050? That largely depends on future emissions. In a low-emissions scenario? The prediction is for sea levels to rise to about 38cm above the 1995–2014 average by the year 2100. In a high-emissions scenario? That can reach 77cm.

Populations are increasingly urbanised. The UN in 2009 and International Organization for Migration in 2015 both estimated ~3 million people are moving to cities every week. The SETO Lab at Yale projects urban land coverage will expand to cover a hair under 10% of the planet’s land. It’s a simple fact that we’re going to be seeing far more storm surges, flooding and land subsidence in coastal cities. Asian cities like Bangkok and Jakarta are under threat, and it’s the same for coastal cities in the US like Miami.

12) For which locations and situations is the Flex Base concept the best suitable?

The FlexBase concept is designed for inland and near shore application. It can handle waves of maximum 1 meter high. In offshore locations, there is always a breakwater needed to reduce wave height and power.

Due to our building process, we don’t need a local dock area because we build directly on the water. In relation to this aspect, we can easily build manmade or natural water bodies without major investments.

The application of the FlexBase concept is not suitable for smaller projects like houseboats due to stability issues. In general, our starting point is 10 x 10 square metres. There is no maximum dimension, depending on the local conditions like waves and water current.

13) Who will benefit the most with the FlexBase System concept?

Depending on the needs and application, this will be city governments and urban planners. They’ll be able to open enormous possibilities to develop water space as a new frontier for cities, creating a new dimension in urban development. Pretty much everyone, whether it’s the public sector, private sector or household sector can benefit from the development of floating infrastructure for near-shore coastal and inland waters.

In terms of social impact, it opens new potential for developing affordable housing stock. For instance, floating housing can be developed in areas with substantial water space, whether it’s along rivers in the city or near-shore environments in coastal cities.

And if you approach it from the water, energy and food security nexus, there’s the potential to combine floating agriculture/aquaculture assets with energy utility microgrids such as solar PV and airborne wind energy (AWE) — wind energy kites tethered to floating structures — so the opportunities to develop highly sustainable and integrated floating complexes that can support the energy and food security needs of coastal communities is immense.

We are closing on our Seed Round in December 2021 and would welcome the opportunity to discuss FlexBase with TSI members who share our vision.